First master absolute commit referencing...

...then learn its relative counterpart! 🤓 In this post I'll showcase the difference between absolute and relative commit references in Git.

In Git there are several ways to target specific commits, some easier to comprehend than others. In short, you have two main options: use absolute or relative commit references. In this post I'll illustrate how the two options differ, and highlight why it's important to familiarize yourself with both alternatives.

Let's go!

Absolute vs Relative references

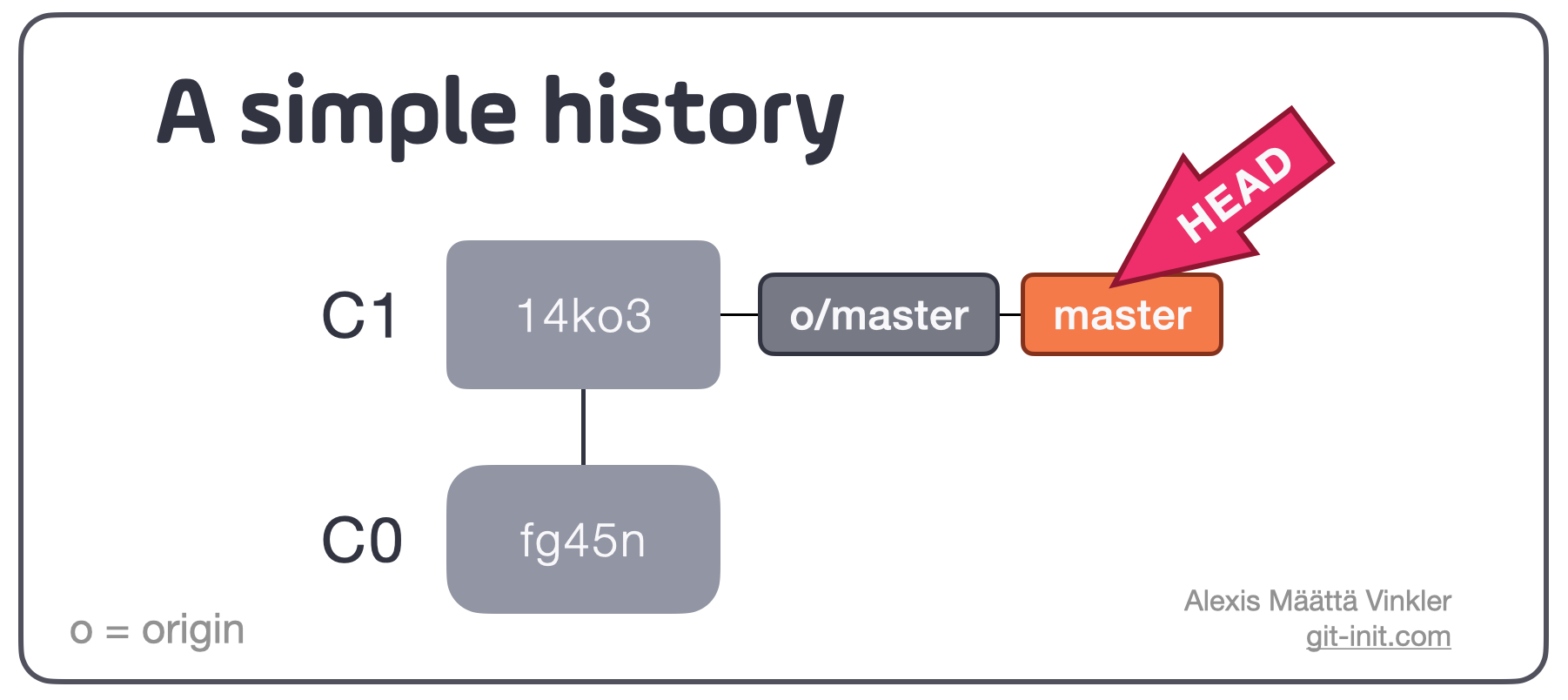

The easiest way to select an arbitrary commit in your history is by using absolute referencing, meaning explicitly selecting the commit using its full SHA hash (or a partial sequence of it). Let's exemplify it with the below history consisting of just two commits on one branch.

Absolute referencing: using explicit SHA

If we for example would like to show the content of commit C1, explicitly using its SHA, any of the below commands would do the trick.

# Using the full SHA

$ git show 14ko32750d81238c424a3889fde067553317e49d --oneline

14ko327 (HEAD -> master)

# or, using a paritial SHA (e.g. first 5 characters)

$ git show 14ko3 --oneline

14ko327 (HEAD -> master)That fact is, as you can see in the last alternative above, the SHA identifier can in theory be as short as possible as long as it uniquely identifies a single commit within your history; in general, 4-7 characters are typically enough to uniquely identify a specific commit.

If we instead wanted to show the content of C0, swapping the above statement with its SHA (fg45n), would work equally well.

With explicit SHA referencing any commit in your history can be targeted, even orphaned ones only viewable through the reflog.

Absolute referencing: using implicit symbolic reference

To constantly retrieve and use the SHA for referencing commits can be quite cumbersome in the long run, so in 90% of the time it's enough to use a symbolic reference such as a branch or a tag instead.

If we again consider the simple two-commit history from earlier, we see that we can target C1 using either master or HEAD as both of them symbolically references 14ko3 implicitly. With that said, the following lines would produce the same outcome.

# Using HEAD as the symbolic reference

$ git show HEAD --oneline

14ko327 (HEAD -> master)

# or, using the branch name

$ git show master --oneline

14ko327 (HEAD -> master)

# or, again using a partial SHA

$ git show 14ko3 --oneline

14ko327 (HEAD -> master)Knowing about how commits can be absolutely referenced, either explicitly or implicitly, is crucial to swiftly navigate your history!

But, even though absolute references allow you to target any commit, it's sometimes not the fastest way to move around. This is particularly true when you just want to select an earlier version from an arbitrary commit – let me introduce relative references!

Relative referencing: using ~ and ^

Let's reconsider the same simple two-commit history from earlier. If again want to show the content of C0, Git has provided us with some relative selectors that can be used in combination with absolut references.